Written by Anasa Fraser.

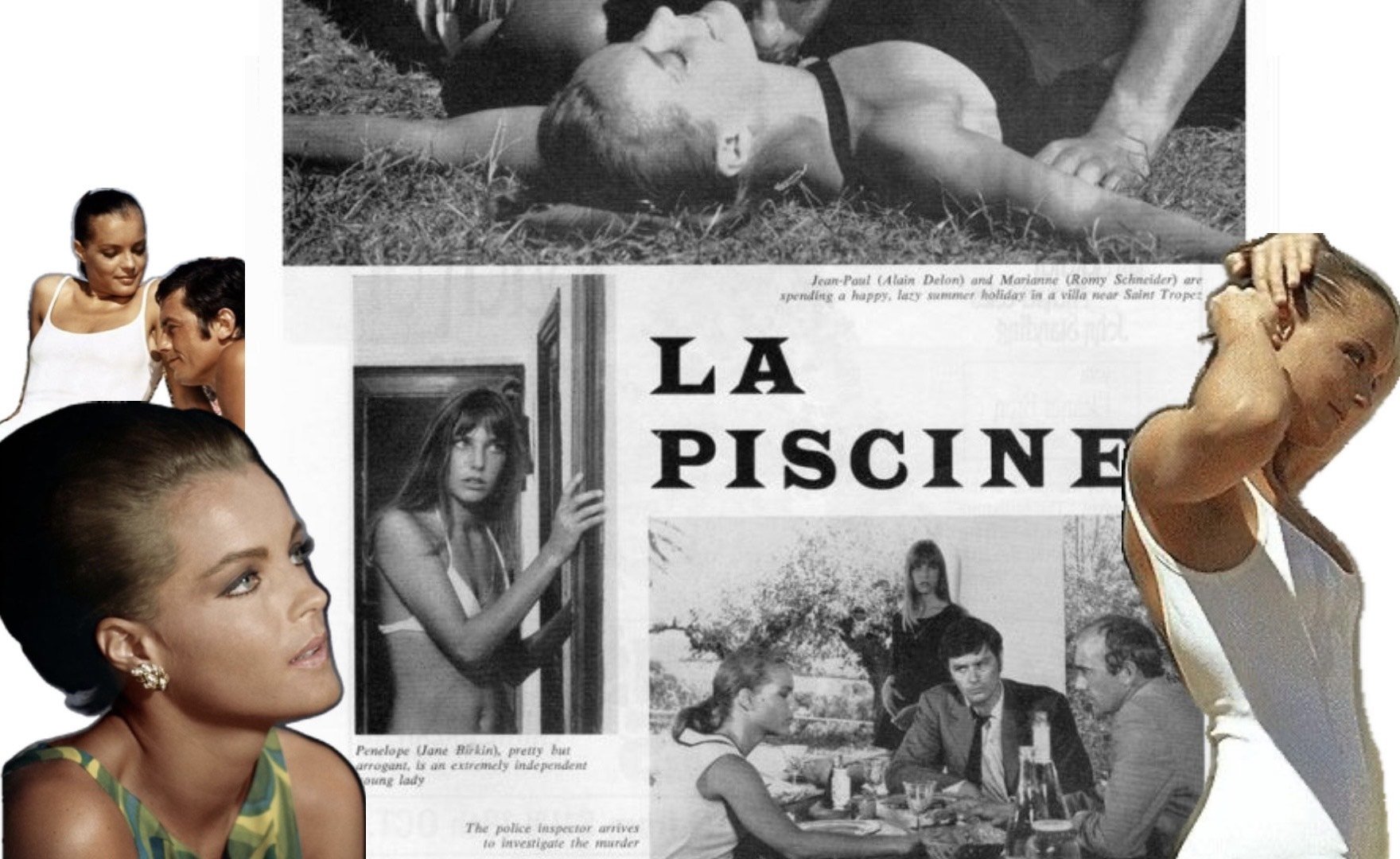

This week's essay examines Jacques Deray's La Piscine (1969), a film that found its way into my viewing rotation. What I anticipated to be a fleeting afternoon watch has instead become a recurring visual study – one that reveals new layers with each viewing, from Deray’s precise camera movements to Michael Legrand’s haunting score.

La Piscine stands as a seminal work in French cinema, not only for its exploration of complex interpersonal dynamics but also for its significant contribution to fashion iconography. Set against the sun-drenched backdrop of the French Riviera, the film serves as a sartorial time capsule, offering viewers a window into the aesthetic sensibilities of late 1960s Europe.

While the film's entire ensemble cast exhibits noteworthy style, it is Romy Schneider's portrayal of Marianne that has left an indelible mark on fashion history. Schneider's character emerges as a paradigm of understated elegance, her wardrobe a carefully curated collection of pieces that epitomize the decade’s shift towards a more relaxed yet undeniably chic approach to dressing.

The cultural memory of La Piscine has become almost synonymous with Jane Birkin's presence – a fact that speaks more to our collective fascination with ingénue archetypes than to the film's complete aesthetic achievement. While Birkin's influence is undeniable (and extensively documented), it's Romy Schneider's characterization that demands closer study. Where Birkin embodies bohemian youth, Schneider crafts something more nuanced: a character whose relationship with fashion feels neither performed nor incidental, but rather innate.

This isn't to diminish Birkin's impact (I mean, look at her, bloody hell) – her style has been so thoroughly analyzed that adding to that discourse feels redundant. Instead, this analysis turns toward Schneider's Marianne, whose wardrobe choices operate on multiple frequencies: as character development, as social commentary, and as an unintentional forecast of fashion's future trajectory. Each piece she wears serves both the immediate narrative and a larger cultural dialogue about femininity, power, and self-presentation.

Through close examination of Schneider's wardrobe throughout the film, we begin to understand how costume can transcend mere clothing to become character architecture. From the precision of her swimwear to the studied restraint of her accessories, each element builds toward a complete portrait of Marianne while simultaneously documenting a pivotal moment in fashion history.

Central to Schneider's wardrobe in La Piscine is the now-iconic white swimsuit, a garment that warrants particular attention for its cultural significance and design ingenuity. This piece exemplifies the paradoxical nature of late ‘60s fashion, straddling the line between modesty and sensuality.

From a design perspective, the suit's simplicity is its strength. Devoid of extraneous embellishments, it relies solely on cut and fit to achieve its impact. This minimalist approach aligns with the broader trend in high fashion of the period, which saw a move away from the structural complexity of the 1950s towards cleaner, more streamlined silhouettes.

The choice of white as the swimsuit's color is particularly noteworthy. In the context of the film, it serves a dual purpose: practically, it provides a stark contrast against the azure waters of the pool, while symbolically, it underscores Marianne's complex character—outwardly confident yet inwardly conflicted.

As the film transitions from day to night, Schneider's wardrobe undergoes a metamorphosis. The nocturnal ensembles serve as integral components of the film's visual narrative, each outfit carefully chosen to reflect the emotional undercurrents and thematic tensions of the scenes in which they appear.

The pale yellow sleeveless dress stands out for the way it subverts expectations of nighttime attire. Its high neckline and simple silhouette create a study in contrasts - a garment that feels both demure and charged with an undercurrent of sensuality. This tension mirrors the complexities of Marianne's relationship with Jean-Paul, alluding to her desire to assert herself within that dynamic.

Schneider's nuanced performance is key to elevating the dress beyond mere costume. Her subtle shifts in gaze and body language imbue the garment with layers of psychological depth, turning it into a symbol of Marianne's struggle to reconcile her public and private selves. The minimalist design allows Schneider's expressive face to command focus, underscoring how fashion can function as a narrative device in service of character development.

In stark contrast to the subdued yellow dress is the dazzling, multi-colored sequined gown that Schneider wears in a later scene. This garment, with its kaleidoscopic array of colors and light-reflecting properties, serves as a visual metaphor for the film's exploration of perception and reality. The dress's deep V-neckline and form-fitting silhouette exude a more overt sensuality than the yellow dress, perhaps indicating a shift in Marianne's emotional state or a desire to keep her partner’s attention. The juxtaposition of this bold, shimmering gown against the muted tones of the evening setting creates a striking visual discord, mirroring the underlying tensions in the narrative. (Unbelievably, Marianne loses her lover to Penelope who is wearing a simple, and can I say juvenile, white tee shirt and jeans— contrasting in both attire and personality.)

A third evening look of note is the green and yellow satin chiffon maxi dress. This garment, with its bold, undulating design, evokes the fluidity of water—a recurring motif in the film. The dress's loose, flowing silhouette contrasts with the more structured designs seen earlier, suggesting a liberation of sorts, physical and emotional. The high neckline and sleeveless cut maintains her sophistication while allowing for freedom of movement (as she gets her lick back in a dalliance with an old flame(!)), a duality that echoes Marianne's complex character.

It is worth noting that throughout the film each look is accessorized with restraint. Schneider wears delicate gold jewelry—thin chain bracelets, long sleek medalions and pinky rings —that complements rather than competes with her attire, and best of all, is repeated throughout the film.

The prevalence of gold throughout serves multiple purposes beyond the obvious (though yes, it does look particularly sublime against sun-warmed skin in that Mediterranean light). From fine chain bracelets to more substantial medallions, each piece builds a visual vocabulary that speaks to Marianne's character without shouting about it. Even the golden grommets on the black swimsuit feel less like design choices and more like evidence of a life thoughtfully curated.

What's particularly compelling is what's missing. In an era when resort wear could veer into the theatrical, Marianne's accessories remain steadfastly understated. No oversized sunglasses, no statement pieces that scream "I summer in Saint-Tropez" – just carefully chosen elements that feel both of their time and somehow outside of it.

The film's single dramatic accessory moment arrives in the form of a sheer black scarf, deployed with precise timing. This brief departure from the established golden palette serves as a subtle narrative punctuation mark – the sartorial equivalent of a well-placed semicolon.

These details, while seemingly minor, construct a character whose relationship with personal style feels neither accidental nor overwrought. Through Marianne's accessories, we understand something essential about her character: here is a woman who knows exactly how much is enough, and perhaps more importantly, how much is too much. In an era increasingly obsessed with documenting style, there's something refreshing about watching someone who simply inhabits it.

The clothing works in service of both narrative and performance – Marianne's fluid transitions between poolside and evening scenes reflect her social adaptability, while the quiet refinement of her wardrobe hints at deeper currents in her character.

The film's costume design demonstrates particular intelligence in its use of color and texture. The progression from sun-bleached daywear to more complex evening pieces mirrors the narrative's gradual descent into psychological complexity. Even the accessories maintain this careful calibration – gold jewelry that catches light by the pool takes on a different significance during night scenes, where it serves as a subtle reminder of the afternoon's warmth.

What distinguishes these choices is their dual nature: they're specific enough to root the film in 1969's French Riviera while transcending pure period documentation. Through Schneider's Marianne, we witness how clothing can articulate character without overwhelming it – a balance that makes the film's sartorial influence feel as relevant now as it did in its own era.

Read more by Anasa Fraser here.

CONTRIBUTE

hello@pagesstudio.net

New York, London, Melbourne, Auckland.

Selected by the Editor.

Six astronauts and cosmonauts – from America, Russia, Italy, the UK and Japan – rotate in the International Space Station. They are there to do vital work, but slowly they begin to wonder: what is life without Earth? What is Earth without humanity?

Together, as they travel at speeds of over 17,000 miles per hour, they watch their silent blue planet, circling it 16 times in a single day, spinning past continents, and cycling through seasons, taking in glaciers and deserts, the peaks of mountains and the swells of oceans.

We glimpse moments of their earthly lives through brief communications with family, their photos and talismans; we watch them whip up dehydrated meals, float in gravity-free sleep, and exercise in regimented routines to prevent atrophying muscles; we witness them form bonds that will stand between them and utter solitude.

Yet although separated from the world, they cannot escape its constant pull. News reaches them of the death of a mother, and with it comes thoughts of returning home. They look on as a typhoon gathers over an island and people they love, in awe of its magnificence and fearful of its destruction.

The fragility of human life fills their conversations, their fears, their dreams. So far from earth, they have never felt more part – or protective – of it.

Synopsis from Penguin.