A column.

Written by Pages Editorial.

For a while I have thought about the idea of access.

Access to culture, to connection.

A continuation on the Schiaparelli lineage, a quick Babitz moment and Georgia O’Keefe. Bliss.

Your access, weekly.

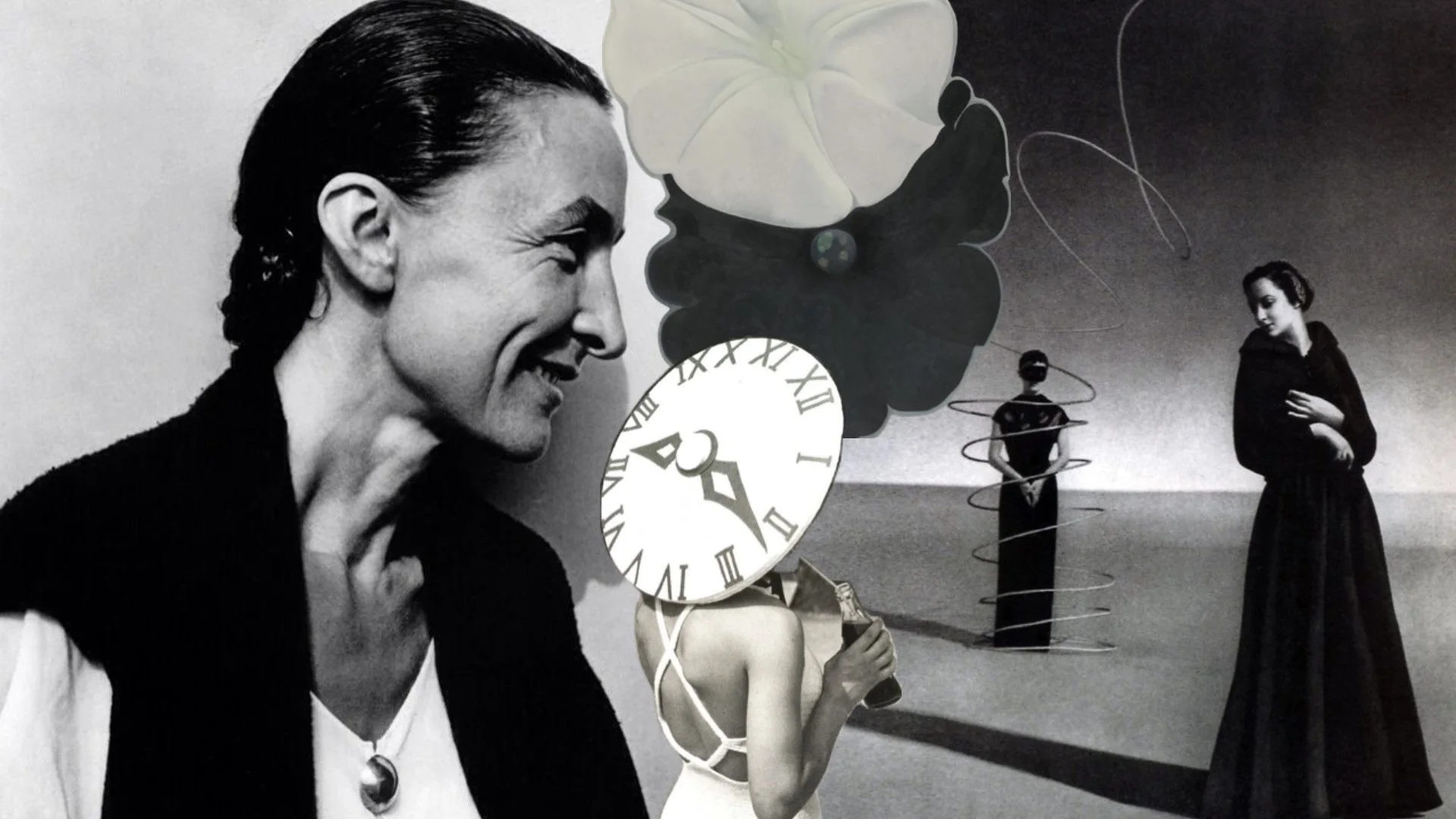

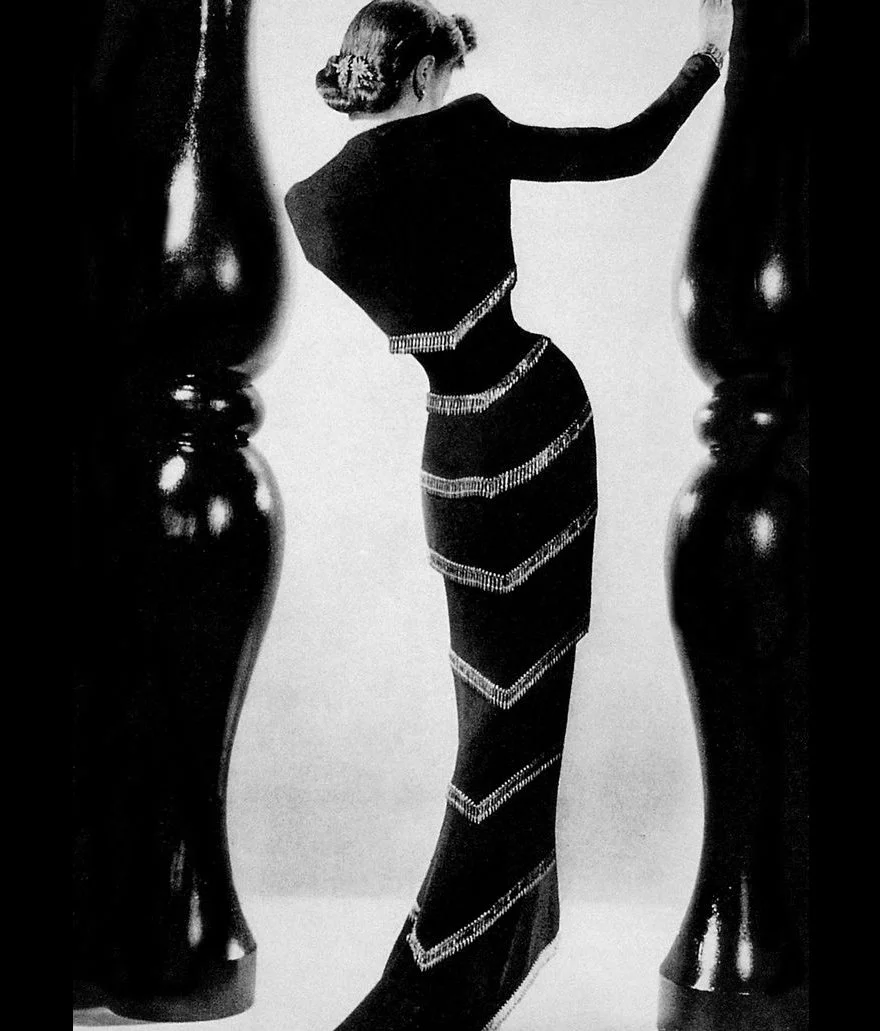

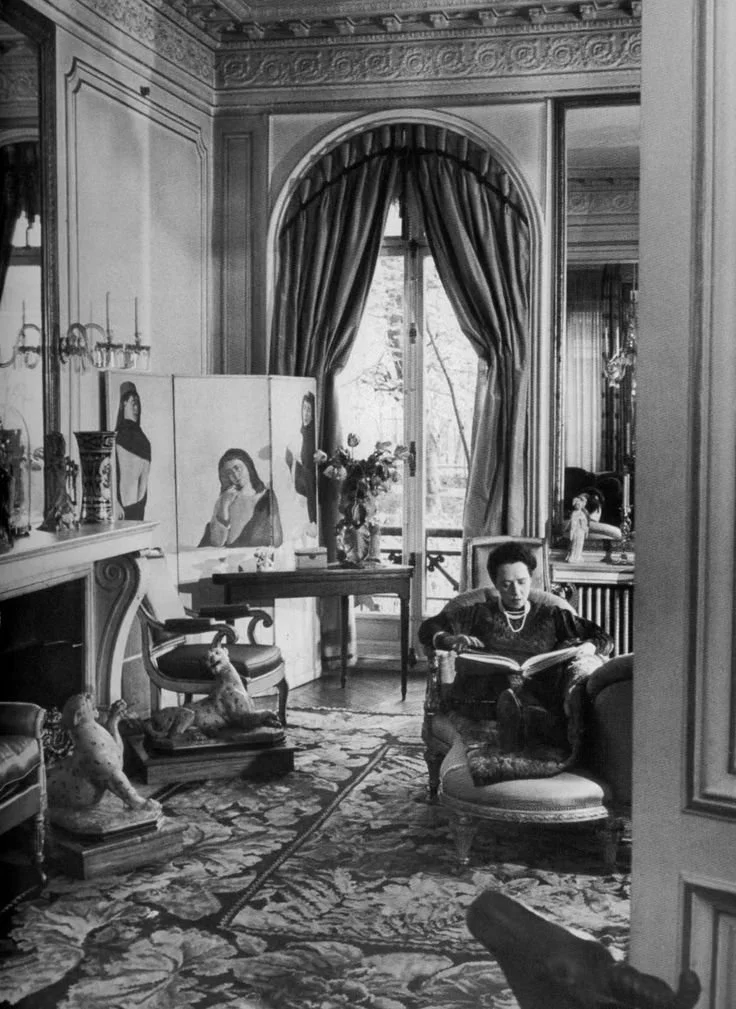

Daniel Roseberry’s recent collection propelled us to unpick the Schiaparelli lineage. What a world it is. Elsa Schiaparelli is one of fashion’s most instructive figures. Her work grew from tension: art and utility, confidence and insecurity. Long before ‘concept’ became a marketing term, Schiaparelli treated clothing as a sitefor ideas.

There is a small, telling story from Elsa’s childhood. As a girl, convinced her face was lacking, Schiaparelli once pushed flower seeds into her ears and nose, in the hope that something beautiful may grow from her. It was a misguided gesture, but a tender one. That instinct to transform and embellish would quietly echo through her work for decades.

Schiaparelli’s immersion in Surrealism gave her language for this instinct. Influenced by the movement’s fascination with the subconscious, illusion, and symbolism, and through close collaborations with figures like Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau, she translated Surrealist ideas into clothing that functioned as wearable thought. Lobsters, skeletons, optical tricks, and cosmic motifs were never gimmicks but visual provocations, asking the wearer to participate in imagination rather than conformity.

What makes Schiaparelli resonate now is her refusal to separate creativity from lived experience. Her designs absorbed politics, feminism, surrealism, and personal vulnerability without apology. She understood that adornment is armor, that wit is power, and that exaggeration reveals truth. In an era obsessed with polish and branding, Schiaparelli’s legacy argues for something riskier. Allowing personal history to shape creative work rather than be erased by it.

To look at Schiaparelli today is to be reminded that originality is not about novelty. It’s about courage.

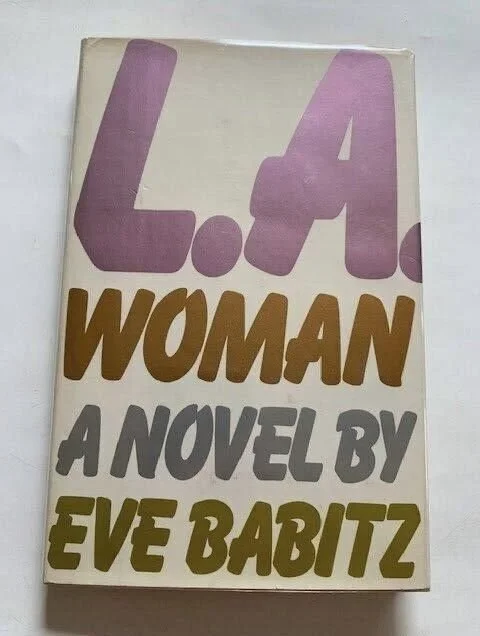

West Coast intelligence. L.A. Women by Eve Babitz is a sharp write up of female life in Los Angeles, written with candor, and a distinctly moving between essays and autobiographical sketches, Babitz writes about desire, ambition, boredom, glamour, and survival as a woman navigating art, sex, and freedom in a city built on illusion. Los Angeles is a collaborator, shaping identities through its heat, sprawl, and promise. With her signature conversational tone and refusal to moralize, Babitz is unapologetically alive in L.A. Women.

AIN’T I GOOD FOR FOR BY YAZMIN LACEY

This percussive piece of music by Yazmin Lacey, an artist born in East London has been playing on repeat in the studio, along with a mish mash of Daniel Richter and Cameron Winter’s Heavy Metal. A bit all over the show really and that’s how we like it. Lacey brings a beautiful soul to the room with her arrangement and tone. Her tour is stopping by London if you in town in March. Listen here.

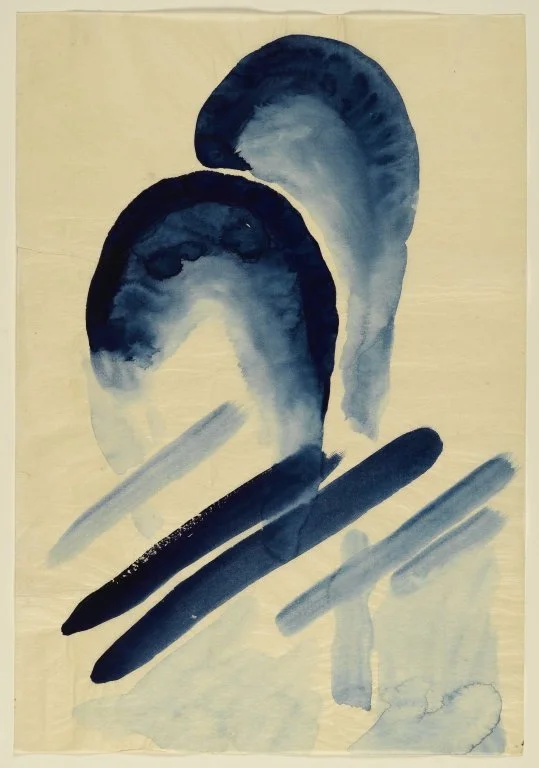

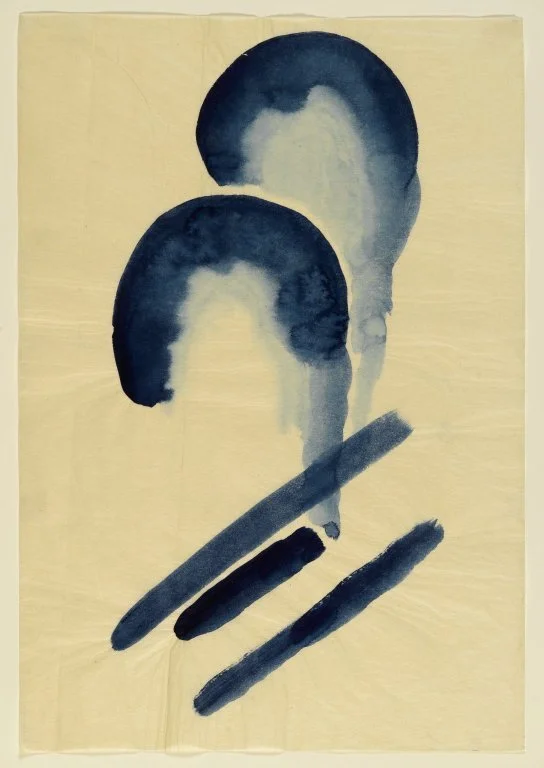

GEORGIA O’KEEFE’S BLUE SERIES

There is a sense that Georgie O’Keefe will be referenced often in this weekly column as her body of work stretched across 7 decades. Georgia O’Keeffe’s Blue series refers loosely to a group of early abstract works she made primarily between 1918 and the early 1920s, when she was moving away from representation and toward a visual language rooted in emotion, sensation, and rhythm rather than objects.

At the time, O’Keeffe was deeply interested in the idea that color could function like music. Blue, for her, was not symbolic in a literary sense but experiential. It held mood, vibration, and interior space. These paintings are about translating feeling into form. Visual equivalents of sound or breath.

Blue allowed O’Keeffe to work with depth and movement. She layered tones from pale, almost translucent blues to dense, dark ones, creating expansion and contraction. The shapes often feel organic but indeterminate. They suggest waves, air currents, bodies, or landscapes.

Works like Blue and Green Music make her intentions especially clear. She spoke explicitly about wanting to paint the way music feels when you hear it, not what it represents. The curves and color shifts move across the canvas the way sound moves through a room. Blue becomes a carrier of rhythm, tempo.

This series also matters because it positions O’Keeffe at the forefront of American abstraction, distinct from her European contemporaries. While many modernists were focused on theory or geometry, O’Keeffe’s abstraction was intuitive and bodily. Blue became a way to claim inner life as a legitimate subject for modern art.

Later, when she returned more overtly to flowers, bones, and landscapes, this sensibility never left her. The Blue series is where she learned how to stretch feeling across space, a skill that defines her work even when it becomes representational again.

To sign up for exclusive access, or to contribute to pagesstudio.net, contact us hello@pagesstudio.net

February

BOOK RELEASES

Coppola

SHORTLIST

CONTRIBUTE

hello@pagesstudio.net

All over the show.